As an art form, Rap remains one of the most dialogical in contemporary media. Both in the sense that it relies on spoken word as an accessible form of expression for both MC and listener, and in the sense that many of its artists interact with, reference and respond to one another, often in the form of heated words and sly digs. The latest in the long line of rap feuds is that between Noname and J Cole. It started after Noname, a Chicago born rapper, poet and activist, ‘called out rappers who were “not even willing to put a tweet up” in the wake of the death of George Floyd’ in a now deleted tweet. Specifically, she seemed to aim at those socially conscious rappers who had ‘made a career’ off of Black suffering and BLM, making a reputation as fierce critics of capitalism’s treatment of Black people both past and present. People had speculated on who it referred to (J. Cole was mentioned, as well as Kendrick Lamar), but it was J. Cole who felt targeted, and in response he released ‘Snow on Tha Bluff’. Whilst like Noname he didn’t mention anybody in particular, these lyrics in particular seem to reference her:

My IQ is average, there’s a young lady out there she way smarter than me

I scrolled through her timeline in these wild times and I started to read

She mad at these crackers, she mad at these capitalists, mad at these murder police,

She mad at my n*ggas, she mad at our ignorance, she wear her heart on her sleeve

She mad at the celebrities, low key I be thinkin she talking bout me

Now I ain’t no dummy to think I’m above criticism so when I see something that’s valid I listen

But Shit, its something about the queen tone that’s bothering me

The track was called out for its sexist tone and misogynoir, though it also had plenty of defenders in the rapper’s fans. J. Cole tweeted the day after that he stood by what he said in the song, though encouraged his followers to follow Nonames twitter account and praised her while playing down his own attributes and intelligence. On Thursday 18th June, two days after the track dropped, Noname responded with 'Song 33', which was produced by Madlib. The song, at a short length of 1:10, brought up many of the criticisms others had, and ‘sees her rap about the poor treatment of Black women by society, seemingly taking aim at Cole for releasing a song about her when he could be fighting against racial injustice’. Whilst there are many pertinent and important issues to discuss in both of these artists' work, what needs to be said about them has already been said, and neither am I qualified to talk about them anyway. But there are a specific couple of lines on Noname’s track that I want to bring attention to:

Yo, but little did I know all my readin' would be a bother

It's trans women bein' murdered and this is all he can offer?

And this is all y'all receive?

These lines sum up the willingness with which Cole’s fans accepted his behaviour and verses. I draw attention to this not only as an example of misogynoir and colourism, but also the relationship between Cole and his fans. I argue that it is a spectacle of socially conscious art, one of the subtle ways in which radical art and radical artists are recuperated into capitalist society and media. It seems important to define what Recuperation is first: it’s a concept introduced by Guy Debord, author of Society of the Spectacle, where radical movements, icons & aesthetics are co-opted and subsumed by capitalist society and are deprived of their revolutionary content in doing so. The Situationist International elaborates:

To recuperate words is really to recuperate what they represent; so that the only activity that words describe is the activity the recuperated words describe. It follows that the true meanings of the words merely become aspects of their false meanings, the true activity they describe merely aspects of their false activity.

The spectacle and recuperation are both different from, and a development of, previous theories of how capitalism commodifies and commercialises art. My fellow writer here at The Commoner, Daniel Moura Borges, has written a good overview of this other process. See here their description on Herbert Marcuse’s theories on the subject:

Herbert Marcuse describes an identical phenomenon in art called repressive desublimation, in which higher culture (in opposition to popular culture) is flattened for commercial purposes under capitalist societies and ends up losing its meaning, its uniqueness and its grit. It turns the purpose of art inside out and makes it a mechanism of maintenance. It could be argued that the commodification and commercialisation of revolutionary ideology is a type of repressive desublimation in which icons of revolution lose their symbolic meaning and become popular icons, devoid of any real significance.

Now where recuperation differs from this is that no hollowing out of revolutionary content, no flattening occurs. The spectacle, which is aimed at creating passive consumers of images and social relations mediated by them, recuperates without having to change much of the message at all. But by putting that message into the hands of the capitalist producers of this content, these messages and artworks have their radical critiques recontextualised in relation to a different purpose. Recuperation differs because the radical work helps maintain oppressive and alienating structures. How this works will become apparent, but first let's look at what form the recuperation of radical art may take.

Now J. Cole may not identify as a radical artist, and he may not necessarily advocate radical politics beyond that of BLM at the time of writing, but he fits into a category of artist, one which is a form of recuperation, that I call the Social Critic. In the field of rap, this takes the form of socially conscious and political rap, in which critiques of prevalent trends and attitudes of contemporary society are produced, and profound statements about the way we live are articulated in sometimes an aggressive and indignant voice. This is not a label or category I think anybody takes up willingly, but one that artists are recuperated in, usually posthumously.

The example par excellence of this is the rapper Tupac Amaru Shakur. Born the child of Black Panthers, named after an Incan revolutionary, and throughout his life a politically radical poet who embodied a range of contradictions before dying a violent death at 25, his legacy was given an afterlife by the selling of unpublished material after his death. This eventually led to a resurrection where he was turned into a hologram at Coachella, an expensive music festival on the west coast of the USA in 2012. His work has been extremely commodified, and descriptions of him now are more likely to describe him as a tragic, brooding street poet who was a condemner of society's woes, rather than an intellectual and leader who inherited the previous generation of radicals’ struggles as well as fighting his own. Fragments of his discography are held up as an incomplete silhouette so that audiences and consumers can project their desires and fantasies onto him. As Jack Hamilton points out:

‘"Dear Mama" is held up to make him a sensitive feminist, which he wasn't, while "Hit 'Em Up" is held up to make him a hyper-violent gangsta, which he wasn't either. In life these contradictions were compelling, the mark of a ridiculously talented artist with a genuinely tormented worldview. But in death it's just incoherence, amplified through artifice and hagiography.

Part of this is reframing his searing indictments of poverty, racial oppression and imperialism into general critiques that offer no alternative. From revolutionary rapper, to social critic.

It can just as much be argued that J. Cole fits into this category as well. His past two albums, 4 Your Eyez Only and KOD, both tackle societal ills and inequality. ‘ATM’ deals with the addictive nature of the accumulation of Capital, whilst the rest of the album KOD deals with the variety of addictions society offers us. The concept of 4 Your Eyez Only concerns a young man dealing with systemic barriers in America, who goes from selling crack to attempting to start a family. Clearly his work is aimed towards representing the struggles of African Americans, particularly working class ones. His is clearly a socially conscious oeuvre of work. But as Cole himself admitted, he doesn’t feel confident as the leader of any Black movements at this time, and that he is not as well read on these matters as he could be. He also doesn’t offer any alternatives to the situation. This is not a bad or problematic thing by itself. A lot of consciousness raising and changing is happening amongst a lot of people, and radical politics usually places great emphasis on change, or the capacity to do so.

But it is also worth remembering the context and system in which Cole makes his work. Rap is a heavily commercialised artform, being part of the modern music industry, and Cole is no different in this regard from any other artist who works within it. Just like Tupac, his records have sold in the millions, his music videos have been viewed by millions on Youtube, and he is a notable, award winning artist. However unlike Shakur, J. Cole is obviously still alive, and remains an active agent in the control of his music and image.

But the logic of the music industry is centred towards profit that is based on the marketing of aesthetic of the artist and art product as much as the music itself. In particular this is where I feel recuperation is evident in Cole’s persona, his work, and his relationship with his fans. Because his persona is that of a socially conscious rapper, this creates a situation as described by Mark Fisher, where instead of his work inspiring others to contribute to change, the work of art instead ‘performs our anti-capitalism for us, allowing us to continue to consume with impunity’. In his tweet thread, despite Cole ostensibly humbling himself and praising Noname, you can find scores of fans praising his humility and taking it as a further reason to support him. When we like an artist because their beliefs match up with our own, we see them as an extension and validation of our self image. And that tricks us into thinking it's meaningful. Like Fisher says:

The role of capitalist ideology is not to make an explicit case for something in the way that propaganda doses, but to conceal the fact that the operations of capital do not depend on any sort of subjectively assumed belief.

Like Noname says ‘[...]this is all he can offer?/And this is all y'all receive?’. The focus of the Social Critic artist turns into the very fact they have made such critiques, rather than the function and purpose of them. We settle for the bare minimum, anything that avoids buyers remorse for our purchased product (or purchased producer). Our engagement with their art centres our enjoyment first and foremost. In the context of Black struggles in particular, this takes on an additionally unsettling implication, as Frantz Fanon notes in The Wretched of the Earth:

Stinging denunciations, the exposing of distressing conditions and passions which find their outlet in expression are in fact assimilated by the occupying power in a cathartic process. To aid such processes is in a certain sense to avoid their dramatization and to clear the atmosphere.

This goes beyond recuperation in a sense, because it leaves us with the conclusion that the way we perform our own politics through the Social Critic artist defuses the situations and contradictions which are being expressed. Or rather, it defuses our reactions and ability to critically respond ourselves because we feel the artist has responded for us. And this goes beyond J. Cole. Arguably, similar approaches by consumers can be found with artists like Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar, Rage Against the Machine, Run the Jewels. All lean into an anti-establishment aesthetic, whilst being a part of the very structures they criticise. The same perhaps could be said of Noname herself, but I would argue that while this does apply to an extent, there are a few crucial differences. What does Noname do that provides alternative action, beyond the Social Critic category.

Aside from not having the same reputation as J. Cole or any of the mentioned artists, Noname also had tried to put her politics in practice as much as possible. She set up Noname’s Book Club, an organisation that in its own words is ‘an online/irl community dedicated to uplifting POC voices’ as well as radical literature. Beyond that it also seeks to raise funds so that it can provide its chosen materials to the incarcerated. The book club has several chapters around the United States. Where Noname offers an alternative to the Social Critic, is that alongside any socio-political commentary she might have in her work, she also works with and for Black communities to educate, or help them educate themselves through the appreciation of literature by BIPOC. This is reminiscent of Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which argues that liberational praxis and education can only come about through the participation of oppressed people in their own liberation. It also bear similarities to Antonio Gramsci’s ‘Organic’ Intellectuals, ‘the thinking and organising element of a particular fundamental social class’.

A similar example in a UK context can be seen in Stormzy, who alongside committing to donating large amounts of personal wealth to Black causes and charities, also curates a publisher for Black voices in Britain that has produced several works by young Black people. Whilst it does this within capitalistic publishing bodies, it is at the very least a serious attempt to create space for Black voices within that industry, and to make best use of a platform with high publicity, and an accessible format of expression. The aim, beyond this, is for ownership of these spaces to be taken up by Black communities, I would argue both amateur and professional.

All of this stresses the need to work with oppressed and exploited peoples. Where this goes beyond the Social Critic is that it does not seek to establish itself as an independent category, and instead aims for the abolition of the distinction between oppressed and intellectual/artist. Since I started writing this article, Noname commented on her response, and articulated the dangers of engaging with using platforms of commercial art distribution as a space for radical politics. This is both because it is open to recuperation, and because it also allows for individualist, egocentric behaviour on the part of the artist. But because it is focused on this same self-reflection and critical thinking, Noname’s ‘organic’ form of political praxis provides at least a small example of the artist's place within the oncoming struggles of the next decade. The question that remains, however, is who will be willing to follow her lead?

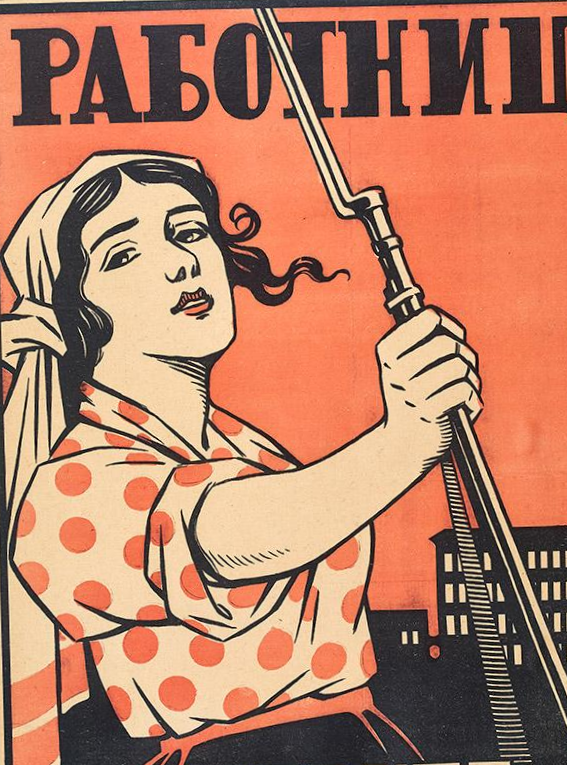

Image source here.

Special thanks for our patrons, Dominic Condello, John Walker, BoringAsian, Mr Jake P Walker, Joseph Sharples, Josh Stead, Dave

If you want to help us reach the funds needed to keep this site up forever, please consider becoming a patron: