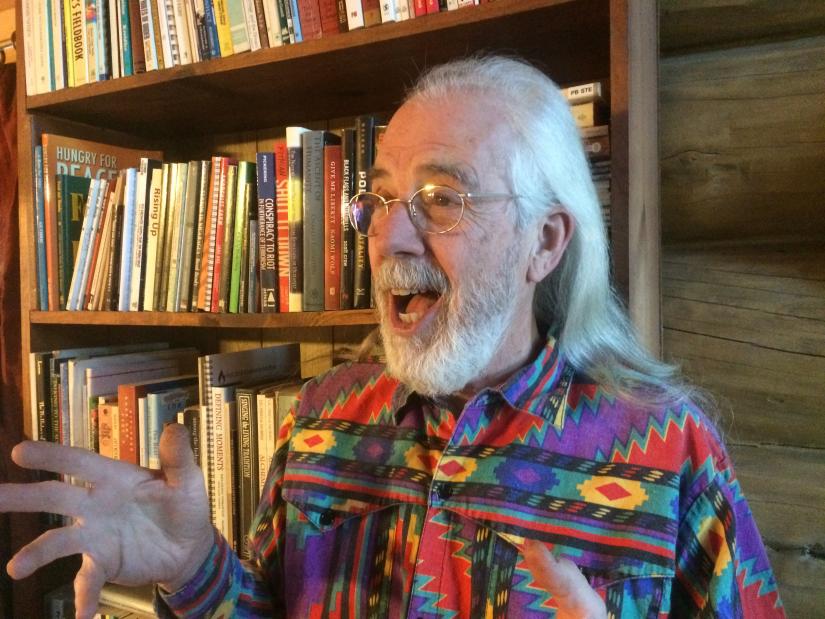

A search for intentional communities brought be to the door of CT Lawrence Butler. He is one of the original founding members of Food Not Bombs in the early 80’s, and has a long and storied career in activism and organising. In addition to direct action and material aid, he has authored two books titled On Conflict and Consensus and Consensus For Cities on the process of formal consensus, that you can find here, along with having taught many workshops on the subject.

Who are you and what are some notable things people might know you for?

CB: Well, my name is CT Butler. I am and I have been a non-violent anarchist and a street activist (I did street activism for twenty years from 1979 to 1999). I participated in well over five hundred protests, got arrested over fifty times, got beaten regularly and beaten unconscious four times during that era. I am a vegetarian chef, I fathered a son, and I’m an early organizer and teacher of polyamory. I was, I guess you could say I still am (I’m sort of retired now) a sacred sex practitioner.

I’ve been a life-long war tax refuser (I haven’t paid my federal tax since 1979), I’m a life-long freestyle dancer. Of course I’ve been a vegetarian my entire adult life. I was an organizer and financier of the pirate radio movement in the 1990’s. I’m a founding member of the Food Not Bombs collective. I have sung in a choir at the great cathedrals of Europe including Notre-Dame in Paris and St. Peters in Rome. I was already a Jesus freak when the term was coined.

I participated in organizing the event for the very first earth day in 1970. I was a boy scout and almost reached the highest rank of eagle. I was a live theatre producer and produced seven plays in Boston, well, one in New York. I was a Cambridge peace commissioner in the mid ‘80’s. I’m a college dropout.

This one’s notable especially now in the last month: I have organized a national protest at the US Capitol, non-violently, and did a protest inside the rotunda where 86 national religious leaders were arrested, and I was one of the primary organizers. I didn’t get arrested in the rotunda, in fact I didn’t get arrested at the event, but I was detained and questioned by the police because of the events of that day.

I’ve heard you talk about a theory concerning the memetic nature of Food Not Bombs. Could you elaborate on that?

CB: That’s a great question. I’ve been thinking a lot about that recently because it’s at the core of the question, 'How did Food Not Bombs start?' I find it somewhat curious that most people don’t ask that question, or if they do they only go as far back as where their local chapter started, but I don’t think most people consider that there was a time, in my lifetime, when I was in my twenties, when there was no Food Not Bombs movement. It didn’t exist.

I was in the original collective, and I’ve been thinking about how it was that the original people that started Food Not Bombs, you know, how and why did we do it. Especially since, at this point in history, forty years later, Food Not Bombs is still active, it’s still happening, it’s world-wide, and there are probably, at any given point or time of day, a hundred or more Food Not Bombs chapters active, possibly many more. We don’t really know because of the nature of its organization. It’s been continuing all this time without any fundraising to speak of (it doesn’t operate using money primarily because it doesn’t require money), and it’s still, pretty consistently, based upon the original concept.

I think it qualifies as a very successful meme, and the thing is, we created it intentionally. It didn’t just spring up, and I don’t think most people realize that. So I can list the six things that we required. At the time we were using the word motif. I’m not sure we were familiar with the word “meme” yet. It existed in literature. It was first coined in ‘76, and this is ‘79 or ‘80. So it’s possible that we were already talking about memes at this point. I’m not going to claim that we were. I do know that we talked about the motif, and that’s a theatre word for me in my theatre background. It was: 'What is the dramatic event or what is the thing that we’re asking people to do, and by doing it will convey the message?' That’s what theatre is. Do this act and it conveys this message. So what is the motif? What’s the overall gestalt? What’s the overall picture?

We had long conversations about how we wanted to start an organization that doesn’t require money (now, it doesn’t require money, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t use it, but it doesn’t require it to function). We wanted to start an organization that’s easy to transmit (the motif itself is easy to transmit): you go out, you collect free food, you cook it up, and you give it to poor people. It’s really easy to get people to understand what that is. It’s an activity that provides material aid. It was directly useful; it was direct action. We were doing something and the fruits of your labour directly impacted somebody else’s life in a positive way. So it was material aid providing food, and that’s a very important point. It uses horizontal structure. This horizontal structure, in our minds, was so it could not be infiltrated, but that also means that there’s no leaders. There’s no person telling anybody what to do. It’s a collective deciding collectively what to do. We wanted people to learn the politics of anti-capitalism and anti-militarism by doing the motif and by doing the activity. If you do the activity on a regular basis you will bang up against society’s rules and regulations that teach you about capitalism, how it operates, and why there are poor people, and when you realize how much money is going into the military, you see the horror and evilness of our society just by feeding the poor.

And last point: it was a gateway to other activist’s issues. It was easy for people to say, 'You know, I want to do something,' and they hear about Food Not Bombs, and what it is is feeding people. That’s a really basic human drive that’s positive and you’re willing to do it, and you might, at that moment, not be aware of how political an act that actually is, so you do it with a kind of naïve notion that it’s just doing good, but that’s great because the truth is that no good deed goes unpunished in society. If you try to do this good deed, then you will have the State come down on you. That’s what happens. It’s by design. It’s built into it as you will, by design, learn about other issues besides food and 'not bombs' (you know, anti-militarism). So those six things had to happen for it to be the meme we wanted to create, and we created Food Not Bombs.

It was actually just a slogan. We were spray painting 'Drop food, not bombs,' on the sidewalks of Boston at the time, and I was working at a Mexican restaurant as a cook (I was a cook at that time and worked up to chef), and other people were working at grocery stores and other restaurants. We were activists, so a lot of us were working at restaurants, and food was a natural idea. What we were doing was collecting food, getting it for free, and at the original Food Not Bombs collective, we were getting the food for ourselves and for other activists. There were a lot of activists in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1980. There were hundreds of them living in collective houses. So we were getting the food and feeding other activists. There was way more wasted food than there were activists to eat it. The slogan in the early months of Food Not Bombs was, “This is the revolution. We’re eating as fast as we can,” because we didn’t want to waste it, and we started giving it to other activists. Our idea was to have it be that instead of working at a shit restaurant job for slave wages and then have to pay for rent, food, and utilities, well, at least we could say, “Save your money for food and eat this free food. Use that money for activism.” That was the original thing we thought we were doing. That’s how naive we were.

There was so much, and we couldn’t eat it all, so we started giving it to, well, who would you think we’d give it to? People who needed it. People who were hungry. People who were poor. We started distributing, and it kept growing. It expanded to the point where we realized it was the motif. It was the thing that we should tell other people to do because it worked really well. It taught you all these great lessons, and it taught us all these great lessons, and it did a really cool thing. That network that I created in 1981 or 1982, in the original Food Not Bombs collective, is still operating in Cambridge to this day under the original name of Food Not Bombs which is 'The Food for Free Committee,' and they’re a nonprofit that’s incorporated and has a board of directors, which was created by what was left of Food Not Bombs (Brian and I) in 1983 and 1984. We incorporated the food distribution part so that it wouldn’t die. We had no idea that Food Not Bombs would become this world-wide movement at that time. Probably a big mistake, but that’s what we did.

What are some other important aspects of the history of Food Not Bombs that you think people should know about?

CB: I would love to address that because I have a unique perspective, obviously. Food Not Bombs as a movement has taken many forms over the four decades that it’s existed. It started as a single household, an anarchist collective in Cambridge. I believe that when we rented the house on 195 Harvard Street in Cambridge, that was the beginning of Food Not Bombs as a movement. We didn’t even call ourselves Food Not Bombs at that point, but six people came together and rented a house together for the purpose of starting a social change movement. That’s what we wanted to do: this meme that I was talking about earlier. So we came together, got a house together, and we moved in on July 1st, 1981 into 195 Harvard Street in Cambridge. That’s where the original collective lived from the very beginning. I don’t think there was a single night where less than six people slept in the house. Immediately it became a hangout spot for a large number of people and at any time during the day there would be a dozen or more people hanging out there, and there were always people there that would stay the night (one night, two nights, or whatever). Sometimes we would have to ask people to leave because they were just sort of there and not really participating. We had a very exciting time.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that year and a half in that house. In the early fall we decided to change our name. We had chosen the name 'The Food For Free Committee,' and that had proven to be a mistake. People didn’t understand what our politics were. They didn’t understand what we were doing. They did understand 'free,' so they would just come and grab whatever they wanted. We changed the name to Food Not Bombs because, like I said, we were spray painting that around town, and we thought that was a great name because we had noted that when there are protests organized by organizations like the Clamshell Alliance, if you didn’t know what it was, then you didn’t know what it was (even though the Clamshell Alliance became famous). What, do you collect seashells?

There were names of groups where it didn’t automatically tell you what they were about, so in the media, they would say there was a group called the October 22nd Coalition. It was an anti-police brutality group back in the 80’s. The media would say, 'Three members of the October 22nd Coalition were arrested today,' and then they would proceed to talk about the police action and what their charges were going to be, and in the entire article there would be no mention of why they were arrested except for they trespassed, disorderly conduct, or assaulting a police officer. There was no mention of police brutality, no mention of why they were there, no mention of anything. We thought, 'This really sucks!' The reason why we’re getting arrested is to get media attention, and then we don’t even get media attention! They don’t tell the story, so we said, 'We’re going to put our politics right in the name of our group.' It’s pretty hard to mistake what Food Not Bombs, as a group, stands for.

We named ourselves that completely unaware of the fact that then, and because of that, the media would say, 'Three people from a loose knit group of anarchists were arrested today.' They wouldn’t use the name 'Food Not Bombs.' Food Not Bombs didn’t appear in the media until well into the 90’s. It was banned. As the media, mostly in the newspapers, unless they were hearing us chant it in the background of a protest, it didn’t get out to the media. They wouldn’t say that we were a group. We were foiled in our attempt.

AB: How did Food Not Bombs evolve throughout the years following the formation of the original collective?

CB: There were many different iterations. The first was a single collective. That disbanded (kind of exploded) for interpersonal reasons. Three of the original members continued doing Food Not Bombs work after it exploded. I continued doing the food distribution network in Cambridge, and we went back to the Food For Free Committee name and became a corporation. I continued doing that in Cambridge in 1983.

Keith McHenry left and went over to Boston, and he started a one day a week Food Not Bombs, which was different. We had never done that before. He was doing one place, collecting food from one location on a particular day, then taking that food to another location and distributing it and calling that Food Not Bombs, which it was, and it was a great thing to do. He did that starting in 1984 I think. 1984 to 1987 in Allston, which is a part of Boston.

I continued doing the food distribution network, but I was still an activist, and I was living alone, and because I had all this food that I was collecting, I started becoming 'the caterer of the left.' I would show up at every protest, rally, conference, and movie fundraiser and provide food (lunch, usually). I would do it for free. All they had to do was call me up, and I would show up. There’s all kinds of great examples. If the blue collar bus drivers were on strike, and they wanted to picket the company all day long, they needed lunch so people wouldn’t leave to get food. I would show up with a hot meal so they could continue picketing all day long. Also, I went to indoor events where they would have a conference, and I would bring lunch for everybody so they wouldn’t have to spend money and they wouldn’t have to leave to get food. I started doing that in 1984, and I was pretty much doing it by myself. I had a roommate in my apartment, a guy named Rob, and he started helping me a lot, and, of course, we called that Food Not Bombs. It was sort of like Food Not Bombs catering. It was all vegan, but we didn’t really use the word vegan back then. I started making a name for myself. I started doing weddings, bar mitzvahs, and things like that because, at the time, there were no other vegetarian caterers. If you wanted to feed one hundred and fifty people vegetarian food, that was it. There was nobody else. What I was doing was basically a real business, but it was all for free, and I just charged a donation all the time, even weddings. It was just whatever they wanted to donate. I used this money to continue doing this network, and then we set up this non-profit.

I continued going to protests. I also brought food to protests all the time. In fact, probably by 1986, if you were in New England, and you were an organizer who wanted to have a protest, and Food Not Bombs wasn’t there, it wasn’t a very important protest. We were basically ubiquitous in New England, and I was doing it all the time. It was a full time job for me. Those were the in between stages.

Then, through a very complex and bizarre set of circumstances, Keith ended up in San Francisco. He had departed Boston in less than positive circumstances. He went to San Francisco and I went to visit him there in 1987. I was like, 'Keith, the weather here is so great all the time that you could do Food Not Bombs here real easy.' You could do it outdoors. You wouldn’t have to find indoor places like in Boston. With a lot of encouragement, Keith drove from San Francisco. I flew with three other people including Rob, my lover at the time, and Eric Weinberger. Eric Weinberger was part of the Chicago Nine. Of course, everybody already knows the Chicago Seven, and they kind of know about the Chicago Eight, but they don’t know about the Chicago Nine. Eric was the ninth. We all were out there and we left all of our equipment, our tables, and three hundred pounds of rice and beans left over from the protest. He took all of that in his little pickup truck back to San Francisco in March or early April, and by the end of May, I talked him into starting a Food Not Bombs in San Francisco. As the saying goes, the rest is history because in August he had been feeding the homeless on the streets for about three months at that point in Golden Gate Park, and he was feeding people there every Monday.

In early August, the mayor, who was a democrat, a liberal, Art Agnos, decided that they couldn’t have homeless people eating lunch in the park because that was just too embarrassing, so he sent the police to shut him down. On August 7th, Keith and two other people were arrested for serving food. The next Monday a larger crowd showed up and the police arrested seven people. The following Monday, the police arrested fifteen. You can see it was beginning to grow. It was doubling each time. The next Monday happened to be labour day. Several hundred people showed up to volunteer for Food Not Bombs. It was a huge event. A lot of people got arrested. I can’t remember the number now, but it was huge. It was so embarrassing and it made international news. In fact, one of the original collective members of Food Not Bombs, a woman named Amy Rothstein (she hadn’t done Food Not Bombs since 1982), had parents touring around Europe that saw the headlines, 'Food Not Bombs Arrested in San Francisco,' and called her up to ask, 'Are you in trouble?' They didn’t know any different. It made the headlines all over the world that activists feeding the poor in Golden Gate Park were arrested (like one hundred or one hundred and fifty). It was a big deal.

I literally jumped in my car in Boston and drove four days straight as fast as I could to San Francisco and got there the next Monday, and the mayor had called off the arrests. He made a truce, but still a hundred or two hundred people showed up. There were a lot more homeless folks getting food as well as supporters. It was the first time in my life that I had that type of experience. I went there and I was with Keith at his house cooking up the food. We had it in his truck. He drove me to the Haight Stanyan. We unloaded the truck with the tables and the food, and then Keith jumped in the truck and drove away. I’m standing there with the tables and the food waiting for everyone to show up because I’m a little bit early, and quite literally, out of the woodwork, out of the shrubbery, behind the trees, down the street, there were thirty different media outlets with microphones out in front jammed into my face. I was paparazzied. They asked, 'What’s going to happen today? Are you going to resist arrest?' I’m like, 'I don’t know.' It was really bizarre.

That was the end of that era of me doing it by myself with just a handful of other people. There was an attempt to start a couple of Food Not Bombs during that era, but none of them took off. Now the San Francisco one was internationally famous and now Food Not Bombs was internationally famous, so the national network started. By 1992, there were enough chapters of Food Not Bombs across the country that we held a national gathering. Now that was interesting because this was a decentralized horizontal structure organization, and Keith and I unilaterally called for a national gathering. Maybe eighty to a hundred anarchists showed up from all over the country (a few from Canada) mostly from the west coast but a few from the east coast. There weren’t that many chapters of Food Not Bombs. There were maybe a dozen or two dozen at most. Keith and I took on the task of organizing this event, which they ultimately loved (it was a beautiful event), but they hated Keith and I for organizing it because we had taken unilateral dictatorial control, and we were 'not good anarchists.' It was one of these conundrums where it was great that we did it, and we were hated and vilified for doing it. That was the first national gathering.

We had another national gathering in San Francisco again in 1995. Maybe eight hundred activists showed up. By that point, there was a more fascistic city mayor who had been the former police chief. His name was Frank Jordan. He was more authoritarian. This coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of the UN, which had been founded in San Francisco, and there’s an obelisk in Civic Center Plaza that has the declaration of human rights on it. It says that every human has a right to food, housing, and the right to protest. We’re in that plaza. That’s where we held our event. Under the shadow of that obelisk, during the fiftieth anniversary of the UN, the police would attack us every lunch and every dinner (we served lunch and dinner in Civic Center Plaza). That was the conference meal. That’s where the conference dinner was going to be too. All the activists from the conference (we had workshops all over town) after meal-time would convene at Civic Center Plaza. We would have trainings. We would set people up to be the servers. The way the police operated was that there would be this huge phalanx of police of about thirty or forty people, and they would move into the crowd around the table and arrest the servers of the food. They wouldn’t arrest the people taking the food and they wouldn’t arrest the other activists. As they were taking people away, they would also take the food. We had hidden some of the food and would bring out the reserve food, set it up again, the police would come back, arrest the next six people, and take that food as well. After about the fourth time, they gave up. At every meal, we could get two or three crews of servers arrested so they could have that experience of getting arrested, going down to the station, getting booked, and getting released. That’s a really important aspect of non-violent direct action. If you’re going to be one, you’re going to have to know how to deal with the courts, the police, and the arrest process. We probably got a couple hundred people arrested that week.

This is part one of a multi-part interview. To be continued.

Special thanks to our patrons, John Walker, BoringAsian, Mr Jake P Walker, Joseph Sharples, Josh Stead, Dave, Bliss, Hol, Aryeh Calvin, Rylee Lawson, Meghan Morales, Kimonoko, Squee, Manic Maverick, Max Dixon.

Please consider giving us your support: