On August 28 in Jakarta, Indonesia, the police deliberately ran over a 21-year-old delivery driver named Affan Kurniawan with an armored truck. Indonesians have been protesting the government and its various scandals since the ascension of Prabowo Subianto, an open authoritarian and son-in-law of the dictator Suharto. Affan's murder was the final spark needed that led to mass unrest and insurrection against the government across the country.

The protests have been covered in detail across anarchist media, including Freedom and Organise! Indonesian anarchists have spoken out directly through Persaudaraan Pekerja Anarko Sindikalis (PPAS) and Perhimpunan Merdeka (see also the PDF linked below). The Commoner interviewed Perhimpunan Merdeka last year.

Two anarchists on the ground, Jungkir and Kimmy, have offered their perspectives on the ensuing protests. You can support the protestors directly by donating to Serikat Napi Lintas-Lapas (Inter-Correctional Prisoner Union).

What is the latest situation with the protests and repression? We understand it has been going on in multiple cities. Has the government tried to shut down the internet or other communications ?

Jungkir: To suppress the rebellion, the government manipulated the weather by causing artificial rain. We also experienced simultaneous disruptions on social media and suspected government interference with Meta. There were no power outages, only signal disruptions at the demonstration site. Nearly a dozen civilians have died, four when the House of Representatives (DPR) building burned down, and six others due to police violence, such as being run over by armored vehicles, police beatings, and tear gas. This wave, unlike previous ones, was very violent and claimed far more lives. The initiative for the demonstrations no longer came from the consolidation of formal organizations like student organizations and labor unions, but instead emerged organically from the general public. This is progress. In the past, it had been difficult for ordinary people to participate in demonstrations because they were suspected of not being part of an official labor organization or student body if they were not wearing alma mater jackets. Furthermore, support for violent actions has increased, whereas in the past, we anarchists were always scapegoated and blamed by society, the press, and the government.

The protests de-escalated on September 3, 2025, due to calls from a group of liberal influencers who argued that the violent demonstrations were a government plot to pave the way for martial law. We believe this analysis is problematic, flawed, and overthinking. The government would suffer significant political and economic losses from the imposition of martial law, so it was an option they were desperate to avoid. However, the calls to halt the protests proved to be very influential, as their followers opposed calls for action in various regions.

Kimmy: Demonstrations took place in 107 locations across 32 provinces from August 25–28, 2025. Following the death of an online motorcycle taxi driver on August 28, the protests escalated. Smaller cities that have so far been almost unexposed to protest actions like "Tolak Omnibus Law" or "Indonesia Gelap," such as Pekalongan, Blitar, Tasikmalaya, Jambi, Palembang, Palopo, etc., have also begun to mobilize.

The government has attempted numerous repressions and restrictions on internet and electricity networks in general. Many big tech companies readily comply with state orders, further reinforcing our long-standing analysis that corporations are not partners in the struggle, no matter how often they claim to advocate free speech. TikTok, one of the most widely used social media platforms in Indonesia, removed its Live feature, previously used by the public to broadcast demonstrations in real time, also known as citizen journalism, while connecting multiple points of resistance. The government claimed that TikTok voluntarily removed the Live feature because it was considered to be broadcasting violence. Ironically, as of September 2, 2025, TikTok re-enabled the Live feature, just at the moment when the escalation of demonstrations had already declined.

At several points where the escalation of demonstrations turned into asymmetric urban warfare, such as in Kwitang (Jakarta) and Bandung, the government carried out total blackouts of electricity and internet networks. Digital repression also targeted anarchist comrades as well as civilians who were labeled as provocateurs of the actions. These attacks took the form of doxxing, online harassment and threats, and even (social media) account breaches.

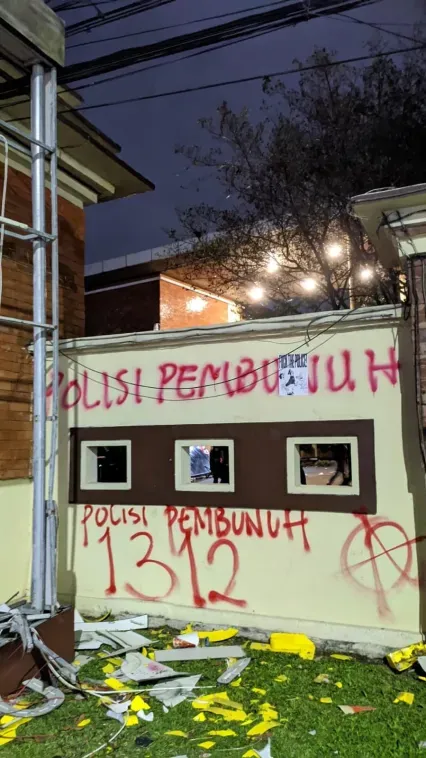

Images from the protest.

Mainstream media reports that the riots were triggered by the killing of a driver, but are there deeper social problems in the background? What are the root causes of the eruption?

Jungkir: The history of uprisings over the past half decade is too vast to fully recount, but at present it has flared up again due to several factors. First, the government imposed massive tax hikes. Second, members of parliament enjoyed a significant salary increase at the same time the President was calling for austerity policy. Third, public statements from the President, the Minister of Finance, members of parliament, and even regional leaders have been harsh, insensitive, and provocative. These factors sparked demonstrations in several cities, beginning in Pati and Bone, and then erupting in the capital, Jakarta, after an online courier was run over and killed by a police vehicle. The following day, the uprisings spontaneously spread to many cities, targeting police posts, police stations, and parliament offices, and today, Saturday, September 30, 2025, they have also extended to the private homes of parliament members and political party offices.

Kimmy: The bourgeois media is attempting to obscure the fact that these mass protests are being framed merely as a reaction to police violence that led to the death of a very young Gojek (motorcycle taxi) driver. In reality, the August protests began for very different reasons. It all started with the plan of the Indonesian House of Representatives (DPR RI) to raise their already exorbitant salaries and allowances, at a time when waves of layoffs, the collapse of the labor market, and skyrocketing living costs have made survival increasingly difficult. Instead, the people were forced to witness the arrogance of the elite. Recently, parliament even increased their housing allowance to nearly ten times the minimum wage, while more than 150 million Indonesians work with incomes below that threshold. Subsidies for the people are being slashed, while funds continue to be poured into officials, the military, and repressive apparatuses.

The insensitivity of Indonesian officials has become a catalyst for the anger of the people who have long been living in crisis. At a time when millions are losing their jobs and the prices of basic necessities continue to skyrocket, they instead make irrational statements—such as calling the people stupid for protesting or claiming that members of parliament deserve high salaries because they are not commoners. The people’s anger today is the culmination of deep disillusionment with those in power, not only over economic issues but also over a crisis of political legitimacy, compounded by the arrogance of public officials who view the people as a burden and a mere commodity of votes.

What was the state of the anarchist movement in Indonesia just before the riots? To what extent are anarchists specifically involved in these protests versus wider anti-government movements? Are left parties trying to take advantage?

Jungkir: Since 2019, we have experienced recurring waves of uprisings. Anarchists have always been steadfast at the frontlines of these rebellions, playing a significant role in organizing at sites of eviction and land struggles, in the student and youth movement, among football supporters, and within the underground music scene. Many anarchists have contributed their energy to street battles, as well as to propaganda through both alternative media and popular culture. However, contributions in the form of writings and original ideas remain relatively scarce. Most of the work has revolved around translating literature from Europe and America, which we feel is highly Eurocentric.

Even so, most of us are not organized or federated. The first national anarchist organization was only initiated in 2023, after we translated the Rio de Janeiro Anarchist Federation (FARJ) book, "Social Anarchism and Organization." We have already held our first pre-congress and are optimistic about our future. Nevertheless, we face strong opposition from anti-organizational anarchists.

There is a socialist united front in which anarchists have not taken part. We have been promoting anti-sectarianism based on ideology, and on the ground we have informally connected and established contact with other activists. Today, the leftist movement in general has reached an agreement around the idea of a people’s council and Democratic Confederalism — except for a small number of purist anarchists.

Kimmy: Anarchists have always been at the forefront of many protests and grassroots organizing. From resisting evictions and agrarian conflicts, to involvement in student and youth movements, football supporter communities, and the underground music scene. Many comrades have contributed their energy to street actions and spread propaganda through alternative media such as zines and independent publications. Though fewer in number, there are also initiatives in historical and anthropological research on anarchism, which have been quite valuable in filling the gaps in knowledge about anarchism in Indonesia.

In recent years, anti-organizational tendencies have grown stronger, sparking an increase in insurrectionary actions within various protests. We value this diversity of tactics and, of course, we gladly support and celebrate direct attacks against capitalist and state institutions that continue to oppress. But we also recognize that the state and capital have consolidated themselves with great strength — meaning that anarchists, too, need to do the same. This requires us to build coordination, consolidation, mapping, study groups, knowledge exchange, and also to carry out the kinds of work often considered tedious: writing, managing social media, keeping track of income and expenses, and handling other technical aspects.

Up to now, anarchists in Indonesia remain far from being truly organized, and as a result are highly dependent on other parties who are often not so friendly toward us. For instance, legal aid for comrades facing repression, street medics, safehouses, and financial support networks are still largely provided by external groups. Militancy must also be sustained by safety nets and logistics — and this is where organization becomes crucial. We attempted a trial-and-error approach during May Day 2025, when many anarchists took on the role of organizing protests in multiple regions, and later managed to save themselves and disappear from the radar thanks to the social support networks we had been building, such as safehouses, financial assistance, psychological support, and more.

Can you tell us a bit more about your efforts to develop a specifically anarchist organization?

Kimmy: We began from the small circles we already had. Some of us knew each other through the same organizations and social movements, through friendships on the internet, or from older anarchist networks. We were inspired by the CNT-FAI, which diligently carried out the so-called boring tasks — the kinds of things that were not considered "militant" or as cool as burning police cars. We held learning circles consistently, even if only 3–5 people attended. We built bonds and treated anarchism not just as an ideology, but as a way of living our lives. From these small circles, we grew. By adding one new comrade at a time, spreading anarchist influence in movements and protests, we eventually managed to gain significant influence within several social organizations while also expanding the number of militants in PM as a political organization.

We are involved in various sectors of social organization — some in labor unions, the women’s movement, student movements, queer organizing, Indigenous struggles, peasant movements, and even prisoner organizing! We usually call this social insertion. Beyond succeeding (and, of course, often failing as well) in influencing social organizations to become more egalitarian, autonomous, and combative, we have also managed to connect different sectors of social movements that had long been operating separately — for example, involving queer activists in labor union struggles, and conversely, pushing unions to stand in solidarity with queer struggles. While this may sound exciting, believe us, it is exhausting, and we are not as big as you might imagine. But we remain consistent and supportive of one another, which allows us to keep growing, even if slowly.

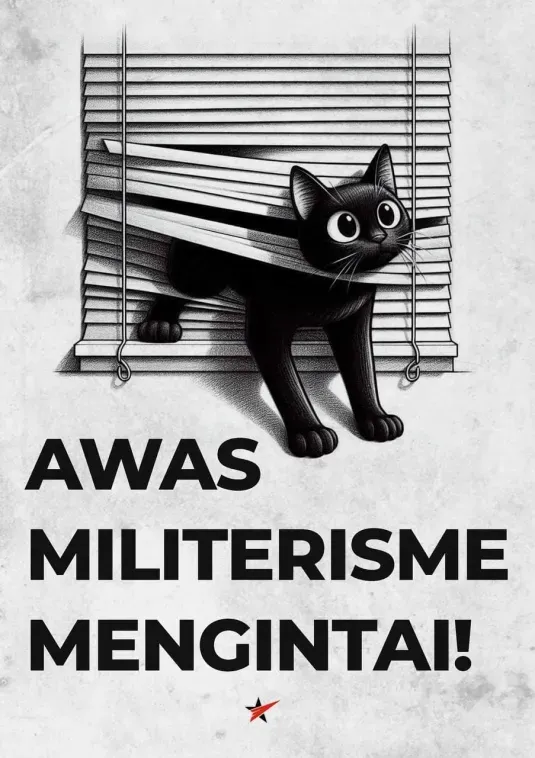

Protest posters provided by Perhimpunan Merdeka.

How has your organization and other anarchists intervened in the social struggles in the current uprising?

Kimmy: Many of our members hold respected positions in student organizations, NGO circles, workers’ unions, and LGBTQ movements in their areas. This gives us greater opportunities to push social struggles so they are not co-opted by political parties or reduced to being “moderate.” Many of our members are also part of protest logistics initiatives that are often overlooked but are absolutely vital — such as street medics and community kitchens. We mobilize donations in a short time, dedicate our energy and spirit to cooking meals for demonstrators, learn basic health techniques to serve as emergency medical teams, connect “fugitives” with our safehouse networks, and much more. Many of us are directly involved in protests, burning and attacking the police, but we also take pride in our consistency in carrying out the so-called boring tasks that are often neglected — yet prove essential in keeping the struggle alive in the face of state repression.

Have there been any "demands" or messages coming out of the protests? Long term, do you see any potential systemic changes coming as a result of this direct action?

Jungkir: There are too many organizations, networks, and groups formulating demands. Even each city has its own unique demands. There are two revolutionary demands: the first from the Perserikatan Sosialis (PS), and the other, a loose, informal, and decentralized network that issued the Declaration of the Indonesian Federalist Revolution 2025, which calls for the dissolution of the unitary state and the DPR system and its replacement with a Democratic Confederalism of thousands of people’s councils for the implementation of direct democracy. Progressive liberals call for a more reformist call, the 17+8 demand. Insurrectionary anarchists, individualists, and post-leftists focus on attacks and street clashes, calling for the destruction of the state and civilization, but without bothering with a platform or program. There is no united front, but we avoid excessive ideological sectarianism. While there’s no single issue, the discourse simultaneously centers on three: tax increases, police violence, and, most importantly, the dissolution of the House of Representatives.

Whether this will lead to systemic change is difficult to answer. The riots in Pati City, Central Java, against tax increases and the resignation of the regent, for example, only resulted in tax cuts, not in the removal of the officials themselves. Even amid widespread criticism and calls for his resignation, the regent remained in office and merely issued an apology. Officials in Indonesia are shameless. The same holds true for politicians, ministers, and even heads of state at higher levels. Today, liberal influencers have formulated the 17+8 demands, with a short-term deadline of September 5. But the government’s only response has been the revocation of certain parliamentary allowances. Yet bloody riots have already occurred and claimed lives. This shows that petitions, demonstrations, civil disobedience, and street clashes alone are insufficient. The only real threat to the state and capital is a general strike, but unfortunately, the labor movement is highly disorganized. Therefore, the people will only be able to channel their accumulated anger through riots or perhaps even lone-wolf terrorism. If this chaos continues, I fear it will lead not to a revolution for systemic change, but to civil war accompanied by separatist movements, or to demoralization. Both are bad options, but we have no choice other than to increase our militancy.

Are these protests related to larger systemic questions about the police and the State in Indonesia? Do perspectives on police map on to similar protests in the US and Europe (e.g., protests after Sarah Everard was killed by UK police, Black Lives Matter...), specifically with a focus on racial/ethnic and gender repression?

Jungkir: Of course. The police here are very corrupt; they will not help the poor but treat officials and the rich with great kindness. Anarchist propaganda plays a role in articulating hatred toward the police, but most of it is an organic expression of lived experiences stemming from class-based disparities and police violence. Several cases of police and military brutality have surfaced. Earlier this year, in February, the punk band Sukatani’s social critique song “Bayar Bayar Bayar” [Pay Pay Pay] went viral after the police intimidated them. The death of Affan, an online transport worker killed by the police, only accelerated the fierce uprising. We believe hundreds of police posts and stations were burned, and clashes erupted in many places. Police and soldiers were even doused with gasoline and set on fire.

Without compromising your security and the security of others, can you tell us a bit about the organization of the current protests? Is there coordination between sites of struggle in the current uprisings?

Jungkir: All civil society organizations, NGOs, and revolutionary political organizations are carrying out their own consolidations or doing so with their allies, but there is no centralized coordination.

Again, without compromising your security and the security of others, do the protesters have strategies for revolutionary self-defense?

Jungkir: None. The issue of strategy has not been widely discussed. There have been some sporadic proposals, but no popular consensus. For the time being, it seems that the discourse on rebellion will be compromised by liberal influencers who are highly popular and influential. There are several popular debates about violent versus peaceful action, but we do not know where this will lead.

Communication from comrades in Indonesia on the “Black Scare”

A silent police operation against the anarchist network is underway.

Just got an update from Bandung city, West Java, Indonesia. Around 40 anarchist suspects have already been arrested. Almost all of them are part of an anarchist network. The police are trying to find out who is handling the funding and the social media admins connected to the network. They will arrest people known to be linked with those social media admins. The West Java Regional Police sweep is not limited to that area. They have already carried out sweeps outside their jurisdiction as well. Some have already been arrested in Makassar, eastern Indonesia and East Java too.

Almost all LBH (Legal Aid Institute) offices under National Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) are not being given access to provide legal assistance. The police will appoint special legal counsels who are related to the police.

You can donate to support the protestors here.